Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy

Main Text

Table of Contents

Morbid obesity is defined as excess weight or body fat to an extent that may have negative effects on health. It increases the risk of developing heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea. Excessive food intake and lack of physical activity are thought to explain most cases of obesity; others are associated with genetic disorders, organic diseases, and psychiatric conditions. Obesity is defined as body mass index (BMI) 30 kg/m2 or higher and is further sub-classified into three groups: BMI 30.0 to 34.9 kg/m2 is class I, 35.0 to 39.9 kg/m2 is class II, and greater than or equal to 40 is class III. The goal of obesity treatment is to reach and maintain a healthy weight. The primary treatment consists of diet and physical exercise; however, maintaining weight loss is difficult and requires discipline. Medications such as orlistat, lorcaserin, and liraglutide may be considered as adjuncts to lifestyle modification. One of the most effective treatments for obesity is bariatric surgery. There are several bariatric surgery procedures, including laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Sleeve gastrectomy is the most commonly performed bariatric surgery worldwide. It is performed by removing 75% of the stomach, leaving a tube-shaped stomach with limited capacity to accommodate food. Here, we present the case of an obese patient who undergoes laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; bariatric surgery; obesity; weight loss.

There has been an alarming rise in obesity rates throughout the world since the turn of the century. In the United States, the prevalence of obesity was estimated at 42.4% in 2017–2018, a greater than 10% increase since 1999–2000.1 Sedentary lifestyle combined with unhealthy diet are the main contributors to an increase in body weight.

Bariatric surgery is a relatively new and upcoming field which has seen major advancements in the past several years. The laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is the most commonly performed surgery performed in obese patients to assist with weight loss. Here, we discuss the necessary steps in preoperative evaluation as well as the steps for performing an LSG.

A thorough history and physical examination are part of the evaluation for undergoing LSG. This evaluation should include a review of past medical and surgical history as well as psychosocial factors that could influence weight loss. Functional status, such as the ability to independently perform activities of daily living, is important to note as well. This is directly correlated with perioperative outcomes, such as adherence to postoperative diet requirements and overall postoperative weight loss.2 The patient should be specifically asked about mental health problems, substance use disorders, underlying eating disorders, and severe coagulopathies as these are all contraindications to surgery. Patients considering bariatric surgery should also undergo a guided weight loss program prior to the surgery as this is a predictor of how reliable a patient will be with lifestyle modifications in the postoperative period.

Physical manifestations of obesity tend to be related to the comorbid diseases associated with it such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and arthritis. A thorough cardiovascular and respiratory exam should be performed to rule out any pathologic manifestations that may hinder the patient’s ability to undergo surgery. This is usually supplemented with an electrocardiogram. An assessment of the patient’s functional mobility is important as well since the patient will need to stay physically active in the postoperative period to assist with weight loss.

There are no specific guidelines regarding the use of imaging in the preoperative period for a laparoscopic gastric sleeve. Patients with prior abdominal surgery should undergo relevant imaging (i.e. CT abdomen with contrast) if it is predicted that the prior surgery may affect the anatomy of the procedure. In addition, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) may be done prior to surgery in patients that have a history of significant gastrointestinal symptoms to rule out any underlying pathology that may affect the patients ability to undergo surgery.3

Signs and symptoms of obesity tend to be related to the comorbid conditions commonly associated with the disease. There is a direct correlation between an increase in body mass index (BMI) and the prevalence of diabetes, metabolic syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea, and cardiovascular disease. As a patient’s BMI progressively increases, their functional status also tends to decline due to an increase in weight-bearing joints and low back pain.4 Due to these comorbidities, obesity is also associated with an increase in age-adjusted mortality rate compared with people who are of average weight.

Patients who have failed other methods of weight loss (diet, exercise, etc.) and who meet the specific criteria (see discussion) for bariatric surgery should consider undergoing LSG. An up to 40% decrease in mortality rate can be seen in obese patients who undergo any type of bariatric surgery compared with those who do not.5

The mainstay of obesity treatment remains to be diet and exercise. The goal is to expend more calories than are consumed. However, when these methods fail, bariatric surgery becomes an option in patients that meet certain criteria (see discussion).

There are multiple types of bariatric surgeries performed to assist with weight loss:

- Sleeve gastrectomy

- Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

- Duodenal jejunal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy

- Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch

- Adjustable gastric banding

Sleeve gastrectomy is the most commonly performed bariatric surgery.6 The popularity of the procedure lies in that it can be performed laparoscopically with an operative time of approximately one hour even in extremely obese patients. In addition, it does not require rerouting of the intestines, minimizing postoperative nutritional deficiencies that would arise due to decreased absorption.6 In most studies, sleeve gastrectomy has been shown to have similar or superior weight-loss outcomes, as well as lower postoperative complication rates, when compared with bariatric surgeries that involve intestinal manipulation.7

In preparation for gastric sleeve surgery, it is important to ensure that the patient is in a state of health where the benefits of surgical intervention outweigh the risks. The comorbidities associated with obesity put this patient population at higher risk for adverse outcomes related to surgery, thus medical optimization (i.e. blood glucose and blood pressure control) may be warranted prior to surgical intervention. Patients with a strong history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) should be cautioned that this procedure often worsens symptoms, and thus the disease is a relative contraindication to sleeve gastrectomy.8

In order to be considered for bariatric surgery, a patient must fall under one of the following categories:9

- BMI > 40 kg/m2

- BMI > 35 kg/m2 with a serious health problem linked to obesity (diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obstructive sleep apnea, etc.)

- BMI > 30 kg/m2 with a serious health problem linked to obesity (gastric band only)

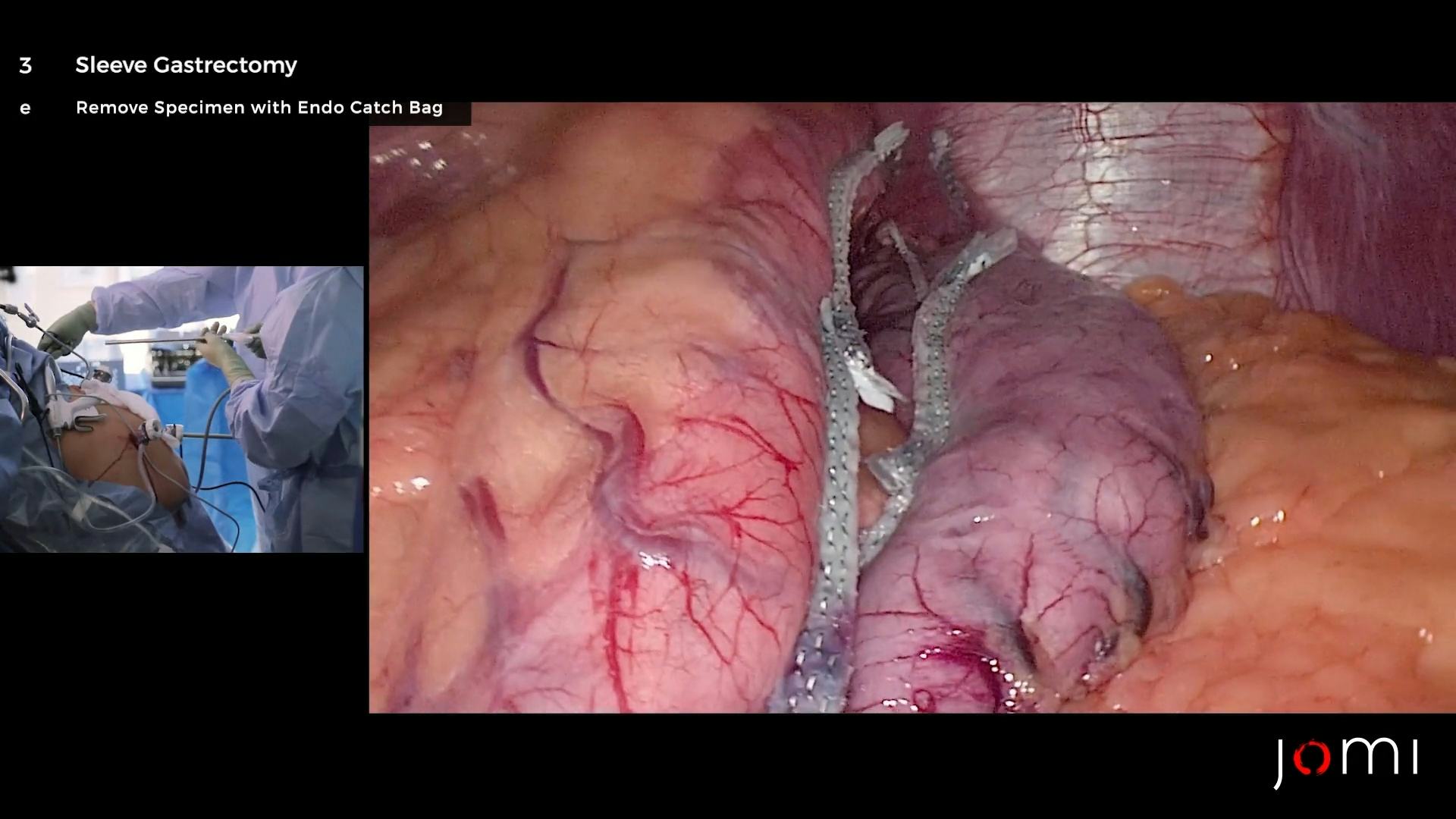

LSG involves resection of the greater curvature and fundus of the stomach. The procedure promotes weight loss through both mechanical restriction and change in endocrine function. Gastric volume is reduced by up to 75%, which diminishes the stomach’s ability to accommodate larger meals. In addition, removal of the fundus, which contains the oxyntic glands that produce ghrelin, results in a decrease in postprandial ghrelin levels.10 Ghrelin is a hormone that stimulates appetite, thus the decreased levels promote weight loss by inducing satiety. Furthermore, studies have shown that LSG also increases glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) levels, which increases insulin secretion and slows gastric emptying.11

LSG has been shown to be highly effective in combating obesity. A retrospective review of multiple studies showed the overall mean estimated weight loss percentage (%EWL) to be 59.3% at 5 or more years.12 Additionally, a prospective observational study involving 179 patients showed that 68.2% of patients with hypertension, 65.8% of patients with type 2 diabetes and 70.4% of patients with obstructive sleep apnea showed resolution or significant improvement of the disease within one year of surgery.13

When compared to other bariatric procedures, LSG has also demonstrated superior outcomes. In one study comparing LSG to laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in severely obese high-risk patients, patients who underwent LSG had greater overall weight loss at two-year follow up.14 In addition, a meta-analysis comparing LSG to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass showed no significant difference in remission of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hemoglobin A1c levels, and 30-day complication rates.15

While LSG has been proven as a highly effective method for weight loss, one must also consider the potential complications that may arise postoperatively. The most dreaded complication postoperatively is a leak from the staple line. In order to avoid this complication, an intraoperative EGD is typically done with injection of methylene blue dye to rule out any leaks. Furthermore, an upper gastrointestinal study using Gastrografin is typically performed on postoperative day one. Stricture is another complication that tends to present in a delayed fashion. The most common site of stenosis is at the incisura angularis.16 Symptoms of stricture include dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, and food intolerance. Finally, patients undergoing LSG have been shown to have an increased incidence of GRED, with one study showing that up to 47% of patients had persistent GERD symptoms at 30 days postoperatively.17

The laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is a major advancement in the field of bariatric surgery. While understanding the risks associated with the procedure, the LSG’s superior outcomes when compared with other types of bariatric procedures have proven it to be a safe and effective method to promote weight loss in the obese population.

- Laparoscopic tray with full set of instruments, including endoscopic gastrointestinal anastomosis staplers

- Staple-line reinforcers

- 5- and 10–12-mm trocars

- Orogastric tube

- Nathanson liver retractor

Nothing to disclose.

The patient referred to in this video article has given their informed consent to be filmed and is aware that information and images will be published online.

Citations

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 360. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020.

- Benalcazar DA, Cascella M. Obesity surgery pre-op assessment and preparation. [Updated 2020 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546667/.

- Shah S, Shah V, Ahmed AR, Blunt DM. Imaging in bariatric surgery: service set-up, post-operative anatomy and complications. Br J Radiol. 2011;84(998):101–111. doi:10.1259/bjr/18405029.

- Perreault L. Obesity in adults: prevalence, screening, and evaluation. UpToDate, Mar. 2020. Available at: www.uptodate.com/contents/obesity-in-adults-prevalence-screening-and-evaluation?search=obesity&source=search_result&selectedTitle=2~150&usage_type=default&display_rank=2.

- Abdelaal M, le Roux CW, Docherty NG. Morbidity and mortality associated with obesity. Ann Translat Med. 2017;5(7):161. doi:10.21037/atm.2017.03.107.

- Hutter MM, Schirmer BD, Jones DB, et al. First report from the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Center Network. Ann Surg. 2011;254(3): 410–422. doi:10.1097/sla.0b013e31822c9dac.

- Lager CJ, Esfandiari NH, Subauste AR, et al. Roux-En-Y gastric bypass Vs. sleeve gastrectomy: balancing the risks of surgery with the benefits of weight loss. Obes Surg. 2017 Jan;27(1):154-161. doi:10.1007/s11695-016-2265-2.

- Stenard F, Iannelli A. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and gastroesophageal reflux. World J Gastroenterol. 2015 Sep 28;21(36):10348-57. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i36.10348.

- Potential Candidates for Bariatric Surgery. (2020, July 26). National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Available at: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/bariatric-surgery/potential-candidates.

- Rosenthal RJ, Szomstein S, Menzo EL. (2020, February 24). Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. UpToDate. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/laparoscopic-sleeve-gastrectomy.

- Dungan K, DeSantis A. (2020, June 4). Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. UpToDate. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/glucagon-like-peptide-1-receptor-agonists-for-the-treatment-of-type-2-diabetes-mellitus?sectionName=GLUCAGON-LIKE%20PEPTIDE%201&topicRef=109435&anchor=H2&source=see_link#H2.

- Diamantis T, Apostolou KG, Alexandrou A, Griniatsos J, Felekouras E, Tsigris C. Review of long-term weight loss results after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014 Jan-Feb;10(1):177-83. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2013.11.007.

- Neagoe R, Muresan M, Timofte D, et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy - a single-center prospective observational study. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2019 Apr;14(2):242-248. doi:10.5114/wiitm.2019.84194.

- Varela JE. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for the treatment severe obesity in high risk patients. JSLS. 2011 Oct-Dec;15(4):486-91. doi:10.4293/108680811X13176.

- Lee Y, Doumouras AG, Yu J, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 2019. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003671.

- Sarkhosh K, Birch DW, Sharma A, Karmali S. Complications associated with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity: a surgeon's guide. Can J Surg. 2013 Oct;56(5):347-52. doi:10.1503/cjs.033511.

- Carter PR, LeBlanc KA, Hausmann MG, Kleinpeter KP, deBarros SN, Jones SM. Association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011 Sep-Oct;7(5):569-72. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2011.01.040.

Cite this article

Meireles OR, Saraidaridis J, Guindi A. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. J Med Insight. 2023;2023(138). doi:10.24296/jomi/138.